Light Coming Through: A Portrait of Maud Morgan

This 23-minute, 16mm color film by Nancy V. Raine (Producer/Co-Director) and Richard Leacock (Co-Director/Cinematographer) is a poetic, lyrical, impressionistic collaboration by Raine, a poet and writer, Leacock, a leading figure in the direct cinema movement, and Maud Morgan, the film’s subject, a Boston-area visual artist who was 78 years old when the film premiered at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts on October 21, 1980.

Morgan’s work is in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Fogg Museum of Art, the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Indianapolis Museum, among others, and in numerous private collections.

MORE ABOUT THE FILM & MAUD MORGAN

I met Richard Leacock in 1973 when I was working at the National Endowment for the Arts in the Public Media (later Media Arts) Program and he was serving on the program’s “panel of experts.” The panel reviewed grant requests and made funding recommendations. In addition to submitting written grant applications, artists seeking support also provided work in progress and/or previous work.

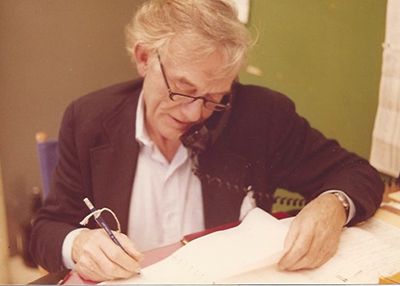

This picture of Ricky at his desk at MIT was taken around the time he served on the Public Media Panel.

This picture of Ricky at his desk at MIT was taken around the time he served on the Public Media Panel.

My job at the panel meetings was to thread 16mm films into the projector in a darkened conference room, take copious notes of the panel discussion, and write up recommendations for presentation to the National Council on the Arts, where final decisions were made. (In those days, a sprinkling of corporate executives, attorneys, bankers and arts patrons served on the Council with luminaries such as Clint Eastwood, James Earl Jones, Rosalind Russell, Billy Taylor, Charles Eames, Eudora Welty, Jamie Wyeth, Judith Jamison, Beverly Sills, and Robert Wise.)

Ricky’s colleagues on the panel included:

What a privilege it was to listen to the panel discussion and observe the respect these amazing artists had for each other’s perspective on the merits of the film or video project before them — there was never enough money to go around and decisions about what to support were not made lightly. The panel took its role seriously and cared about supporting new, often unproven, talent, as well as established artists. Ricky was especially perceptive, sensitive and articulate in these discussions – his wit and good humor were treasured by everyone.

The panel met twice a year and the program staff looked forward to it and the informal dinners afterward, which Ricky often cooked at the Georgetown home of the program’s director, Chloe Aaron. He was an excellent cook – he respected his ingredients and loved the process. He told me that his love of cooking was the result of spending so much time as a child in the kitchen with the cook on his father’s Canary Island banana plantation.

After I moved to Cambridge (1978) Ricky asked me if I would like to produce a documentary he’d been asked to do about the Boston artist, Maud Morgan. I leapt at the opportunity after I met Maud, who became a mentor and close friend. He prepared this meal for Maud, Marissa Silver, the film’s gifted editor, and me in his apartment in Cambridge, when we were working on Light Coming Through. I had many meals at Ricky’s place while we were working on the film. He always made sure there were flowers on the table – and a loaf of handmade bread.

After I moved to Cambridge (1978) Ricky asked me if I would like to produce a documentary he’d been asked to do about the Boston artist, Maud Morgan. I leapt at the opportunity after I met Maud, who became a mentor and close friend. He prepared this meal for Maud, Marissa Silver, the film’s gifted editor, and me in his apartment in Cambridge, when we were working on Light Coming Through. I had many meals at Ricky’s place while we were working on the film. He always made sure there were flowers on the table – and a loaf of handmade bread.

The painting Maud was working when Ricky filmed her in her studio is featured on her biographical page at Maud Morgan Arts, a community arts center in Cambridge, MA named after her.

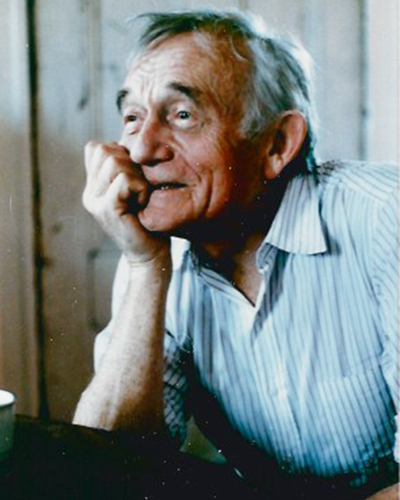

This is one of my favorite pictures of Ricky, taken in the kitchen of his apartment during the years we worked together in Cambridge – he turned sixty while we were shooting the fishing sequence in Quebec. It captures his compassion, accessibility, curiosity, wit, and sense of fun. The last time I saw him was in Paris in the late 1990s, after he had moved to France and was living with the French filmmaker Valerie Lalonde. He was happier than I had ever seen him.

This is one of my favorite pictures of Ricky, taken in the kitchen of his apartment during the years we worked together in Cambridge – he turned sixty while we were shooting the fishing sequence in Quebec. It captures his compassion, accessibility, curiosity, wit, and sense of fun. The last time I saw him was in Paris in the late 1990s, after he had moved to France and was living with the French filmmaker Valerie Lalonde. He was happier than I had ever seen him.

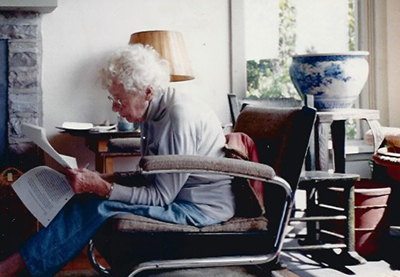

Maud never stopped stretching creatively — this is a picture (below) of her working on her memoir, Maud’s Journey: A Life from Art, in her children’s cottage in Quebec, Canada. It was self-published in 1995, when she was 93.

She told me that when she got a rejection from Doubleday in 1992, written by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (then a Senior Editor), she had already had 45 refusals.

She told me that when she got a rejection from Doubleday in 1992, written by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (then a Senior Editor), she had already had 45 refusals.

“I was mesmerized,” Jackie wrote, “— every page is suffused with grace, simplicity and ingenuousness. You have written of your life and surroundings with an effortless charm and freshness that lingered with me long after I put your work

down.” But it would be a difficult book for Doubleday to do successfully, she continued, “in these lean times for publishing.”

“After Jackie’s letter,” Maud told me, “I finally published it myself.” This was so typical of Maud – to turn a rejection into a positive.

Art New England (1995 Dec/Jan 1996, Volume 17, Number 1) reviewed the book, describing it as a “strange and amazing little book.” From the review:

“Atrociously written but hard to put down, it is utterly candid, often poignant, funny, and full of improbable intersections with history. I catch myself at times thinking of Morgan as a sort of Yankee Forrest Gump: like Gump’s, her life reads as a skewed primer on American history, or rather in her case, on the social history of American art. But her story is also a personal one, of a privileged tenacious woman who refused to stop growing.”